Agility

Tomáš Werner

23.09. – 18.10.15

curated by Tereza Jindrová

A word about the exhibition:

1) Dog agility is a type of sport in which dogs strive to overcome various obstacles such as hurdles, walls, viaducts, broad jumps, pipe tunnels, collapsed tunnels, slaloms, dogwalks, teeter-totters, A-frames, pause tables, etc. You and your dog can engage in agility competitively, or purely for fun at public dog playgrounds. As various magazines and clubs point out, success in agility primarily depends on coordination between the dog handler and the dog. Most dogs enjoy sport simply because they like movement and learning and are happy to be with their master. The same is true for people; however, people also take pleasure in achieving success (e.g. victory), which is something foreign to dogs. A dog is happy when he has made his master happy.

2) Animals have been present in visual arts since time immemorial and represent one of the very oldest of motifs. Dogs have appeared in the upper echelons of society since at least the Middle Ages – they seconded their masters and mistresses in portraits, but we also see them as staffage in the majority of genre tableaux. Last but not least, there are independent portraits of popular aristocratic dogs.

3) Today, the presence of animals in art is perceived with ambiguity, their depiction capable of evoking impressions of a certain infantility and even populism – “Everyone likes animals, after all,” or “Animals can essentially intrigue everyone.” In the “extreme” position, it might even represent an ecological art, to which admirers of “pure” art have trouble relating due to its extra-artistic objectives and, sometimes, its connection to activism. On the other hand, there is the use of animals as such, be it as preserved bodies or actual living beings. The presence of animals in art typically generates strong reactions. We have grown accustomed to people, whether children, unemployed individuals, members of various minorities, etc., participating. Participation on the part of animals, however, elicits a greater degree of controversy. While the men in the project by Santiaga Sierra hold the falling wall voluntarily and were paid for doing so, the coyote does not get to decide on his presence in the gallery.

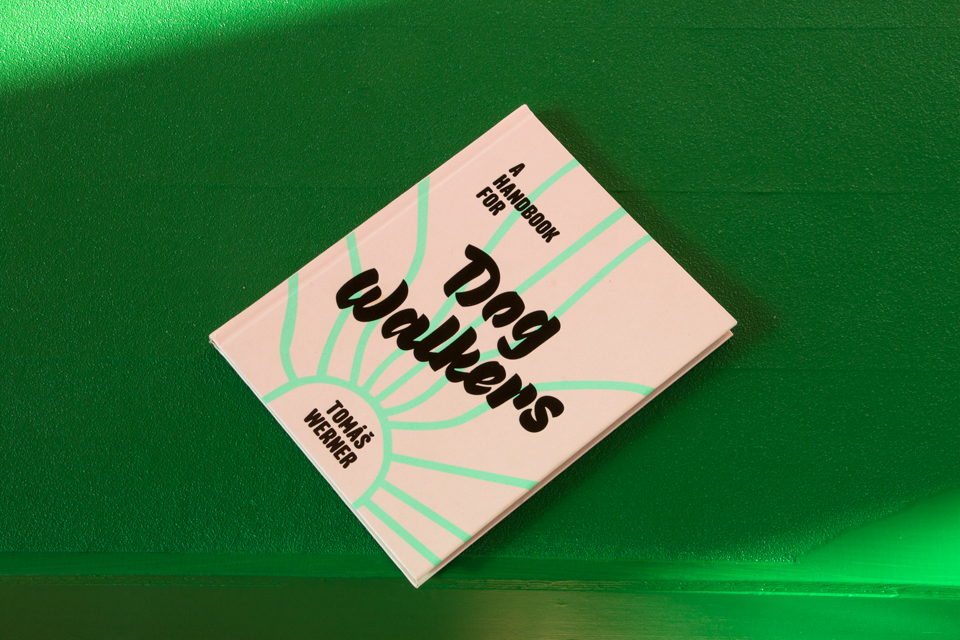

4) Tomáš Werner has divided his exhibition at Entrance Gallery into two parts. In an unconventional move, he has situated in the entry hall monumental black-and-white prints of select images from the series A Handbook for Dog Walkers, which is also presented in photographic book form and originally was to serve as the core of the exhibition. This cycle came about when Tomáš was looking after a Pomeranian by the name of Q for his friend in Florida. Q is the perfect model. He poses just about anywhere and is an iconic dog – simply put him somewhere; he always looks perfect. Dog-object.

5) The main part of the gallery testifies to an entirely different approach. Here, the dog is present in a far more personal sense, yet he isn’t visible. He changes from object to subject. Tomáš spent over a week sharing the gallery with a two-year-old Jack Russel Terrier named Tino and, to a large degree, adapted his work to the presence of the dog. The result is a site-specific installation arranged according to an arbitrary color key with emphasis on formal purity. This time, the distinctive space of Entrance Gallery has been transformed thanks to colored light, both by day through the windows and in the evening through filters on the lamps. But what does the spatial installation of objects in basic geometric shapes actually represent? It comprises homemade obstacles for dogs that are based on those used for small and medium breeds in dog agility and can be put to use by interested parties.

6) Is the artist using the gallery space in an attempt to imitate something from the extrinsic, “inartistic” reality (dog playground) and instill in it formal qualities to guide the observer to esthetic contemplation? In part, perhaps, but greater significance lies within movement in the exact opposite direction: not to primarily show the art-loving public the hitherto unknown beauty of agility obstacles but, conversely, to transform the gallery in a genuine dog playground. In other words, if you have not come with a dog who knows how to appreciate such things, the exhibition will, in essence, remain incomplete to you because, more than the presence of observers, it demands the presence of dogs. Thus, we arrive at the idea of canine subjectivity.

7) In his contemplative work entitled Why look at animals?, John Berger describes the relationship between pets and their owners: “The pet offers its owner a mirror to a part that is otherwise never reflected. But, since in this relationship the autonomy of both parties has been lost (the owner has become the-special-man-he-is-only-to-his-pet, and the animal has become dependent on its owner for every physical need), the parallelism of their separate lives has been destroyed.” Yes, Tomáš’s installation demands the presence of dogs, but that in turn is unthinkable without the presence of their owners. The domesticated dog “reflects” its owner, and the owner has grown fond of him because “the pet completes him, offering responses to aspects of his character that would otherwise remain unconfirmed. He can be to his pet what he is not to anybody or anything else.”

8) Therefore, the dog as a companion to man (as with other pets) forms a peculiar category. It is an independent entity yet is fundamentally bound to man. The majority of animals on this planet, however, still live in the wild. What is their subjectivity like? There is currently an event taking place in Pilsner, the European Capital of Culture for 2015, called “Why speak with animals?”, during which interspecies couples (man and his animal) will be selected for an imaginary Noah’s Ark. According to this idea, animals are essentially so dependent upon man that if the world were to be flooded, only those with some type of relationship to man would survive. In his essay, Berger describes the relationship between man and the “original” animal: “No animal confirms man, either positively or negatively. The animal can be killed and eaten so that its energy is added to that which the hunter already has. The animal can be tamed so that it supplies and works for the peasant. But always its lack of common language, its silence, guarantees its distance, its distinctness, its exclusion, from and of man. Just because of this distinctness, however, an animal’s life, never to be confused with a man’s, can be seen to run parallel to his. Only in death do the parallel lines converge. With their parallel lives, animals offer man a companionship which is different from any offered by human exchange. Different because it is a companionship offered to the loneliness of man as a species.”

9) I view the redirection of the observer’s attention to the animal (the dog) and the propagation of its relationship to man (the dog handler) as crucial aspects of this exhibition. Propagation of this dependence can open a new way of thinking for us on the topic of animal subjectivity as such and on the idea that the “human animal” is not surrounded in this world only by “talking objects” (which curator Václav Janoščík is certainly giving consideration to in the duo of exhibitions entitled Návrat objektu (Return of the Object) and Neklid věcí (Disquietude of Things) but also by other animals. We could take the question from Pilsner, “Why speak with animals?”, (the dog handler really does speak with his trained dog in giving him commands when running the obstacle course, but that is one-way communication), and reformulate it to “How do you listen to animals?” or “What are animals telling us?”